Understanding Core Tax Structures

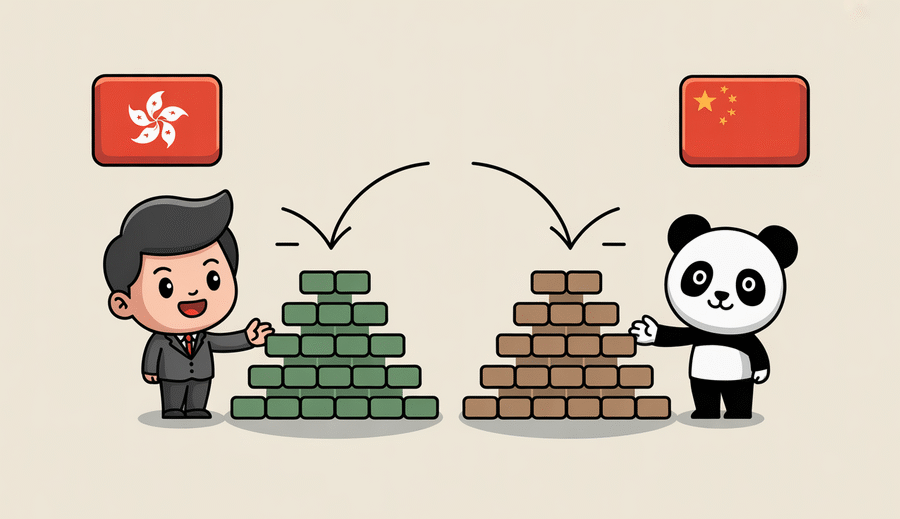

When evaluating corporate tax environments, the foundational tax structures of Hong Kong and Mainland China present a significant divergence. Hong Kong operates under a territorial tax system, a principle central to its appeal for international businesses. Under this system, only profits sourced in Hong Kong from a trade, profession, or business conducted within the territory are subject to Profits Tax. Income derived from sources outside Hong Kong is generally not taxable, irrespective of whether it is remitted into Hong Kong. This focused approach offers clarity and predictability, particularly for businesses with extensive international operations, as their primary tax concern is demonstrating the non-Hong Kong source of their income. The territorial principle simplifies compliance for many multinational corporations using Hong Kong as a regional hub without generating substantial local-source revenue.

In contrast, Mainland China employs a more comprehensive tax framework primarily based on residency and source. Resident enterprises in Mainland China are subject to Corporate Income Tax (CIT), also known as Enterprise Income Tax (EIT), on their worldwide income. Non-resident enterprises are taxed only on income sourced within Mainland China or income effectively connected with a permanent establishment (PE) in China. This system is comprehensive as it taxes the global income of residents and utilizes complex source rules and PE concepts for non-residents, aligning more closely with international tax norms than Hong Kong’s purely territorial model.

These differing core principles fundamentally shape how taxable income is defined and calculated in each jurisdiction. Hong Kong’s system necessitates meticulous analysis of profit sources, requiring businesses to demonstrate a clear nexus or lack thereof with activities conducted within Hong Kong to determine taxability. This can involve detailed factual inquiries depending on the business’s nature. Mainland China’s system, while considering source for non-residents, places significant emphasis on residency status for domestic entities, taxing their global earnings and requiring comprehensive reporting related to worldwide income. This fundamental difference in the scope of taxation is the primary factor influencing tax obligations and planning strategies for companies operating across these two interconnected, yet distinct, economic regions. Understanding these core structures is the essential first step in comparing their respective corporate tax landscapes.

| Feature | Hong Kong | Mainland China |

|---|---|---|

| Core Principle | Territorial Taxation | Residency & Source-based Taxation |

| Scope of Taxation | Income Sourced in Hong Kong Only | Worldwide Income (Residents); China-Sourced Income (Non-residents) |

| System Character | Simplified Sourcing Rules, Predictable for non-HK income | Comprehensive, Detailed Rules for Residents & Non-residents (incl. PE) |

Standard Corporate Tax Rates Compared

Expanding on the foundational structures, the standard corporate tax rates in Hong Kong and Mainland China reveal a key difference in potential tax burden, serving as a crucial consideration for businesses. Understanding these standard rates is essential before exploring nuances like deductions or incentives.

Hong Kong utilizes a straightforward two-tiered Profits Tax rate system. For assessable profits up to HK$2 million, the tax rate is 8.25%. Profits exceeding this HK$2 million threshold are taxed at the standard rate of 16.5%. This tiered structure effectively offers a reduced rate for small and medium-sized businesses, enhancing Hong Kong’s attractiveness for startups and smaller operations without complex application processes. The system is generally applied uniformly across most sectors, contributing to high transparency.

In contrast, Mainland China’s standard Enterprise Income Tax (EIT) rate is 25%. While this applies to most enterprises, the Mainland system is characterized by significant variations and preferential rates targeting specific industries or activities. For example, High and New Technology Enterprises (HNTEs) often qualify for a reduced rate of 15%. Additionally, smaller enterprises with low profits may benefit from effective rates significantly lower than the standard 25% on taxable income thresholds, reflecting policies designed to support small businesses and innovation.

Beyond these standard and industry-specific rates, both jurisdictions leverage targeted incentive programs to attract investment. Mainland China has numerous Special Economic Zones and development areas offering tailored tax reductions, sometimes leading to substantially lower effective rates for qualifying businesses within those regions. Hong Kong also provides specific tax concessions, although these are often tied to particular business activities (such as treasury operations, shipping, or certain financial services) rather than broad geographic zones in the manner of Mainland China’s SEZs.

Here is a comparison of the standard corporate tax rates:

| Jurisdiction | Standard Corporate Tax Rate |

|---|---|

| Hong Kong | 8.25% (first HK$2M assessable profits) / 16.5% (above HK$2M) |

| Mainland China | 25% (Standard Rate) |

Ultimately, while Mainland China’s 25% standard rate is higher than Hong Kong’s top rate of 16.5%, the widespread availability of preferential rates based on industry, size, or location means the effective tax rate for a company in Mainland China can vary considerably. Hong Kong’s system, with its clear two-tiered structure, offers greater predictability based primarily on profit level.

Deductions & Allowances Landscape

Moving beyond headline tax rates, the availability and nature of deductions and allowances significantly shape a company’s effective tax burden. Both Hong Kong and Mainland China offer various tax relief measures, but their focuses and mechanisms differ, reflecting distinct economic priorities and tax philosophies.

Hong Kong’s tax system provides specific allowances primarily focused on capital expenditure. Businesses can claim deductions for capital expenditure incurred on qualifying assets like plant and machinery used for trade or business purposes. Initial allowances and annual allowances, based on asset type, are designed to enable companies to recover the cost of these investments over time, thereby reducing taxable profits. This approach aligns with encouraging tangible investments in business operations.

Mainland China, conversely, strongly emphasizes fostering innovation through generous incentives such as R&D super deductions. Companies incurring qualifying research and development expenses can often deduct more than 100% of these costs against their taxable income. For example, every Yuan spent on eligible R&D might allow a company to deduct ¥1.5 or even ¥2, significantly lowering their tax liability and actively promoting technological advancement and innovation within the economy.

Regarding depreciation allowances, both jurisdictions permit the deduction of asset costs through depreciation over their useful life. Hong Kong specifies rates for different asset types, particularly focusing on plant and machinery via annual allowances. Mainland China also permits depreciation based on asset categories and prescribed minimum useful lives, generally employing methods like the straight-line method. The specific rules and rates vary, impacting the timing and total amount of deductions claimable over an asset’s life cycle.

Understanding these nuances in deductions and allowances is crucial for effective tax planning. While Hong Kong offers straightforward allowances on capital assets, Mainland China strategically employs deductions, especially for R&D, as a tool for economic development. The specific impact on a business depends heavily on its operational activities and investment profile in each location.

| Deduction/Allowance Type | Hong Kong Approach | Mainland China Approach |

|---|---|---|

| Capital Expenditure | Specific allowances for qualifying plant & machinery (Initial & Annual) | Rules for fixed assets depreciation and certain capital costs |

| R&D Costs | Standard deductions for revenue expenditure; specific rules for capital R&D | Generous ‘Super Deductions’ allowing deduction exceeding 100% of cost for qualifying expenses |

| Depreciation | Annual allowances based on asset type and prescribed rates | Depreciation rules based on asset category and useful life, commonly straight-line method |

Tax Compliance & Administration

Navigating the regulatory landscape is a critical business consideration, and tax compliance presents distinct differences between Hong Kong and Mainland China. The administrative burden and processes can significantly impact a company’s operational efficiency and resource allocation. Understanding these variations is crucial for effective tax management.

Hong Kong is widely recognized for its relatively streamlined tax filing process. Companies primarily focus on the annual Profits Tax return. The system is based on self-assessment, with clear deadlines and established procedures. Tax authorities typically issue returns annually, requiring businesses to file within a specified timeframe, usually supported by audited financial statements. This straightforward approach contributes to the city’s reputation as an easy place to conduct business from a tax perspective.

In contrast, Mainland China’s tax compliance environment is considerably more complex and multi-faceted. Beyond Corporate Income Tax, companies must manage Value Added Tax (VAT), withholding taxes, and potentially other local levies. A cornerstone of the Mainland system is the VAT invoice management system centered around the “Fapiao”. The Fapiao is not merely a receipt; it is a legally mandated official invoice essential for claiming input VAT deductions and substantiating business expenses for CIT purposes. Proper management, issuance, and collection of Fapiaos are paramount for compliance and audit readiness. Filing frequencies are often monthly or quarterly, depending on the tax type and business size.

The penalty structures for non-compliance also differ. In Hong Kong, penalties are generally statutory and relate to late filing, underreporting, or failure to keep adequate records, typically resulting in fines or additional tax charges. Mainland China’s penalties can be more severe and wide-ranging, potentially including significant fines, interest charges, blacklisting through the social credit system, restrictions on business operations, and even legal repercussions for serious or repeated offenses, particularly those involving tax evasion or misuse of the Fapiao system.

To illustrate the key administrative differences, consider the following comparison points:

| Aspect | Hong Kong | Mainland China |

|---|---|---|

| Key Compliance Focus | Annual Profits Tax Filing | Multiple Taxes (VAT, CIT, etc.), Frequent Filings, Fapiao Management |

| Invoice System | Commercial Invoices sufficient for most purposes | Official Fapiao System is mandatory and crucial for deductions/reporting |

| Administrative Complexity | Relatively Streamlined, Self-Assessment Focus | More Complex, Detailed Reporting, Integrated Tax/Invoice Technology Systems |

| Penalty Severity | Statutory Fines, Additional Tax | Broader Range, Can Impact Business Status, Legal Action for serious breaches |

Navigating these systems effectively requires a thorough understanding of local regulations and often necessitates engaging with local tax professionals to ensure accurate and timely compliance.

Foreign Business Implications

Navigating the tax landscape in Hong Kong and Mainland China presents distinct considerations for international businesses, particularly concerning cross-border transactions and presence. One crucial difference lies in the treatment of passive income flowing out of these jurisdictions to foreign entities.

Hong Kong generally imposes no withholding tax on dividends, interest, or royalties paid to non-residents, provided the income is not locally sourced business income. This absence of withholding tax on passive income often offers a significant advantage for foreign investors receiving such payments.

In contrast, Mainland China typically applies a standard 10% withholding tax rate on such payments to non-resident enterprises. This rate applies unless a lower rate is stipulated by an applicable double tax treaty between Mainland China and the recipient’s jurisdiction of residence.

To further clarify the withholding tax difference for common passive income types for non-residents:

| Income Type | Hong Kong (Non-Resident) | Mainland China (Non-Resident, before treaty) |

|---|---|---|

| Dividends | 0% | 10% |

| Interest | 0% (unless sourced in HK & related to HK business) | 10% |

| Royalties | 0% (unless sourced in HK & related to HK business) | 10% |

Both jurisdictions have extensive tax treaty networks, but their primary impact differs. Mainland China’s treaties are often vital for foreign businesses to reduce the standard 10% withholding tax rate on passive income. Hong Kong’s growing network is beneficial for clarifying tax positions and avoiding double taxation on active business profits or capital gains, but the general absence of withholding tax on passive income often makes treaties less critical solely for receiving dividends, interest, or royalties. The scope and specific provisions of these treaties require careful examination based on the specific counterparty jurisdiction.

Understanding the rules around Permanent Establishment (PE) is also paramount for foreign businesses operating in these regions. Hong Kong’s territorial principle means a foreign company is generally only subject to profits tax if its profits are sourced in Hong Kong. A physical presence or operational activity might not necessarily trigger a tax liability if the profits’ source is determined to be elsewhere according to specific sourcing rules. Mainland China, however, has broader PE definitions, aligned with international norms (OECD/UN models), where certain activities, such as a fixed place of business, construction sites exceeding a specific duration, or dependent agent arrangements, can constitute a PE. Establishing a PE in Mainland China leads to Corporate Income Tax obligations on profits attributable to that PE. These varying thresholds for creating a taxable presence necessitate careful structuring and operational planning for foreign entities engaged in activities within either or both jurisdictions.

Recent Policy Shifts & Trends

The tax landscape in both Hong Kong and Mainland China is dynamic, continuously evolving in response to global trends, domestic economic priorities, and international cooperation initiatives. Staying informed about these shifts is crucial for businesses navigating their tax obligations and strategic planning.

One significant trend impacting both jurisdictions is the global movement towards greater tax transparency and combating base erosion and profit shifting (BEPS). Hong Kong is actively developing its framework for implementing the OECD’s BEPS 2.0 initiatives, particularly Pillar Two, which aims to ensure large multinational enterprises pay a minimum level of tax regardless of where they operate. Businesses exceeding the specified revenue threshold must monitor Hong Kong’s legislative progress closely, as it will introduce new compliance obligations and potentially impact their tax calculations in the territory.

Mainland China continues to refine its tax policies to support strategic national goals, with a notable focus on fostering innovation and growth in the technology sector. Recent adjustments include introducing or enhancing specific tax breaks and R&D super deductions for qualifying high-tech enterprises and strategically important emerging industries. These incentives aim to stimulate domestic innovation, attract investment in advanced technologies, and strengthen China’s position in key global industries, directly benefiting companies operating or entering China’s tech industry.

Furthermore, both jurisdictions are grappling with the complexities of taxing the digital economy, particularly concerning cross-border data flows and digital services. As data becomes increasingly valuable and business models rely heavily on its movement and digital platforms, traditional tax rules face challenges. Developments in this area could lead to new interpretations or specific rules for taxing digital services and data-related income, impacting a wide range of businesses involved in cross-border digital transactions.

The following table summarises some key recent areas of focus:

| Jurisdiction/Focus | Key Recent Shift/Trend | Brief Description |

|---|---|---|

| Hong Kong | BEPS 2.0 Implementation (Pillar Two) | Developing framework for global minimum tax impacting large multinational enterprises. |

| Mainland China | Tech Industry Tax Incentives & R&D Support | Enhanced targeted breaks and deductions to foster innovation and growth in technology sectors and strategic industries. |

| Cross-border Focus | Digital Economy & Data Flow Taxation | Addressing complexities of taxing digital services and data transfer across borders; increased scrutiny on cross-border related party transactions. |

| Compliance | Increased Tax Administration Modernization | Leveraging technology for compliance, data analysis, and enforcement in both jurisdictions (e.g., Mainland China’s Golden Tax System updates). |

Monitoring these ongoing shifts is essential for businesses. They reflect fundamental changes in how profits are taxed globally and domestically, driven by digitalization, international cooperation, and national development strategies. Staying informed helps businesses anticipate changes, manage risks, and identify potential opportunities within their compliance framework.

Strategic Planning Considerations

Optimizing business structure is paramount when navigating the distinct corporate tax landscapes of Hong Kong and Mainland China. Strategic decisions regarding the location of key functions can significantly influence tax liabilities and overall operational efficiency. Understanding the nuances of each jurisdiction’s tax system allows businesses to structure operations in a way that aligns with tax objectives while supporting growth and operational needs.

One crucial area for strategic consideration is supply chain structuring. The physical flow of goods, locations of manufacturing facilities, and distribution points all have significant tax implications. For instance, how goods are procured, processed, or distributed through entities located in Hong Kong or within Mainland China’s various tax zones (including Free Trade Zones or Special Economic Zones) can affect import duties, VAT, and corporate income tax. Careful planning around the location and function of entities involved in procurement, production, and sales is essential to leverage the differing tax treatments, potentially minimizing tax leakage across the value chain from source to end customer.

Another critical element is the strategic placement of intellectual property (IP) ownership and management. IP-rich businesses must carefully evaluate where to legally own and manage their valuable assets. The tax treatment of royalties received or paid, along with the tax implications of developing, holding, or transferring IP, differs between Hong Kong and Mainland China. Placing IP strategically can potentially optimize the tax burden on IP-related income, taking advantage of specific regimes, incentives, or favorable withholding tax environments available in one location over the other. This decision can influence everything from R&D location decisions to licensing agreements and the overall profitability derived from intangible assets.

Furthermore, the decision of where to establish a regional headquarters (RHQ) or principal hub demands careful tax, legal, and operational analysis. A regional headquarters often consolidates management, administrative, and financial functions, as well as potentially procurement, R&D, or sales coordination. The tax implications of these intercompany activities, including complex transfer pricing considerations for transactions between the RHQ and affiliates, vary significantly. Analyzing potential tax incentives available for RHQs in certain Mainland Chinese cities or leveraging Hong Kong’s relatively straightforward tax system and lack of withholding tax on outbound payments for regional management activities are key steps in determining the most tax-efficient and operationally effective location for coordinating regional operations across the Greater China region and beyond. These structural decisions are fundamental to effective long-term tax planning and operational efficiency.