Hong Kong’s Approach to Taxing Capital Gains

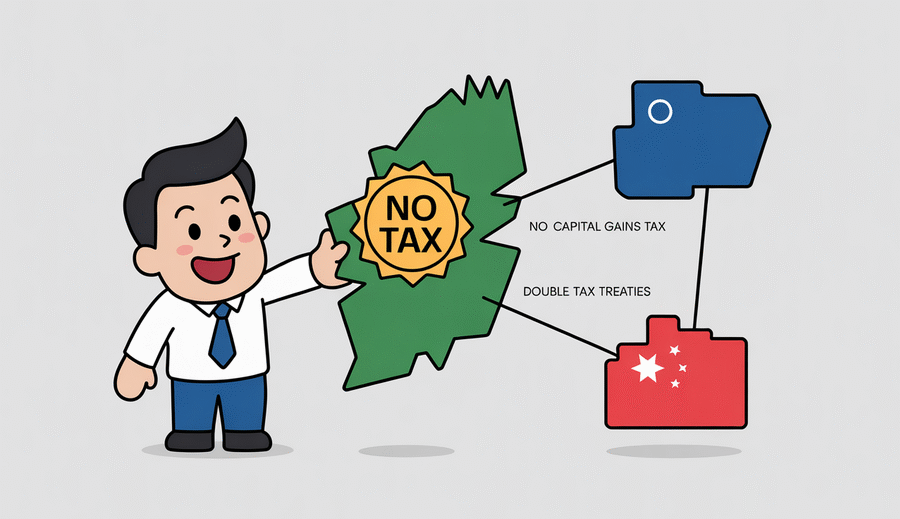

Hong Kong operates under a territorial basis of taxation, a system distinct from the worldwide or residence-based models prevalent in many other jurisdictions. This principle dictates that only income considered to arise in or be derived from Hong Kong is subject to profits tax. A key consequence of this approach is that, as a general rule, capital gains are not taxed. Gains realized from the disposal of assets are typically regarded as capital in nature and thus fall outside the scope of Hong Kong’s profits tax, provided the taxpayer is not engaged in a business of dealing in such assets. This characteristic is a fundamental element of Hong Kong’s appeal as an international financial centre.

This stands in notable contrast to the tax frameworks found in numerous member countries of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). Many OECD nations levy specific capital gains taxes on profits derived from the sale of various asset classes, including shares, real estate, and intangible property. Such taxes can significantly impact multinational entities and global investors engaged in cross-border transactions. While international tax discussions often focus on income, the differing treatment of capital gains remains a critical point of distinction, offering Hong Kong a competitive edge compared to many developed economies.

The absence of a general capital gains tax under its territorial system provides Hong Kong with a strategic advantage, particularly for international businesses and cross-border investors. For entities structuring regional investments, establishing holding companies, or facilitating asset disposals, Hong Kong offers a tax-efficient platform by eliminating the layer of taxation on capital appreciation that would typically apply in many other jurisdictions. This clarity and favorable treatment of capital gains simplifies investment structures and can enhance returns on capital, positioning Hong Kong as an attractive hub for managing global assets and executing international transactions. It draws capital flows seeking predictability and efficiency regarding capital realisations.

Fundamentals of Double Tax Treaties

Double Tax Treaties, commonly known as DTTs or DTAs (Double Taxation Agreements), are cornerstone instruments of international taxation. These bilateral agreements play a crucial role in facilitating cross-border economic activity by preventing individuals and businesses from being taxed twice on the same income or capital by two different countries. Without DTTs, the potential for double taxation could erect significant barriers to international trade and investment, hindering economic growth and discouraging global mobility. By providing clear rules and certainty regarding taxing rights, DTTs substantially reduce compliance burdens and mitigate tax risks for international participants.

A fundamental purpose of any DTT is the precise allocation of taxing rights between the two contracting jurisdictions. For various categories of income or capital, the treaty specifies which country holds the primary right to tax (typically based on source or residence) and under what specific conditions. A treaty may grant exclusive taxing rights to one country, allow concurrent taxation with a mandated mechanism for relief (such as a tax credit or exemption), or impose limits on the withholding tax rates that can be applied at source. This intricate process ensures that income generated in one country by a resident of another is subject to appropriate taxation while protecting the taxpayer from being fully taxed by both nations.

DTTs typically address a broad spectrum of income streams that frequently cross national borders. Standard examples include dividends (profits distributed by a company to its shareholders), interest (income derived from loans or debt instruments), and royalties (payments made for the use of intellectual property like patents, trademarks, or copyrights). For each of these income types, a DTT will usually outline the maximum rate of withholding tax that the source country can impose, often lowering the domestic rate, and clarify how the recipient’s country of residence should treat that foreign income for tax purposes, commonly by providing relief from double taxation. While these specific income types are standard inclusions, the treatment of other items, such as capital gains, can differ significantly from one treaty to another.

Hong Kong’s DTT Network and Structure

Hong Kong has proactively developed an extensive network of Double Tax Treaties (DTTs) to support and facilitate cross-border trade and investment. As of late 2023, this network comprises over 41 comprehensive agreements with key economies globally. These treaties are designed to provide certainty to investors and businesses by clearly defining the taxing rights of each jurisdiction over various income types and ensuring relief from potential double taxation. This broad coverage underscores Hong Kong’s commitment to fostering an open, predictable, and favourable tax environment for international enterprises and individuals.

Accessing the benefits provided by these double tax treaties typically requires proof of tax residency in Hong Kong. The Inland Revenue Department (IRD) issues a Tax Residency Certificate (TRC) to eligible individuals and entities who are considered residents of Hong Kong for tax purposes under the terms of the relevant treaty. This certificate is a vital document that must be presented to the tax authorities in the treaty partner jurisdiction to formally claim treaty relief, such as reduced withholding tax rates on dividends, interest, or royalties, or other specific protections afforded by the agreement. The TRC application process is a standard procedure designed to ensure that treaty benefits are accessed only by genuine Hong Kong residents.

A key characteristic of most of Hong Kong’s comprehensive double tax treaties, particularly relevant in the context of capital gains, is the general absence of specific articles dedicated to the taxation of capital gains. While DTTs commonly include detailed provisions allocating taxing rights over gains derived from the disposal of various asset classes (e.g., immovable property, shares, business assets), the majority of Hong Kong’s agreements do not feature such specific capital gains clauses. This structure means that the taxing rights over capital gains realised by a Hong Kong resident from sources within a treaty partner country are usually governed solely by the domestic tax laws of that partner country, without a specific treaty override or allocation rule for capital gains. This approach aligns directly with Hong Kong’s domestic tax system, which does not impose a general capital gains tax.

Capital Gains Implications for Foreign Investors

When foreign investors engage with Hong Kong, particularly concerning assets or investments capable of generating capital gains, a specific situation arises due to Hong Kong’s territorial tax system. While Hong Kong itself does not impose a capital gains tax, this does not automatically exempt a foreign investor from CGT obligations. The primary interaction occurs between Hong Kong’s source-based taxation principle and the residence-based or worldwide taxation systems prevalent in many other jurisdictions. An investor resident in a country that taxes its residents on their global income, including capital gains, will likely remain subject to their home country’s CGT rules on gains realized from Hong Kong-related investments, irrespective of Hong Kong’s nil rate. This scenario means the investor is typically not subject to CGT in the source jurisdiction (Hong Kong) but remains potentially liable in their jurisdiction of residence.

Furthermore, foreign investors must carefully consider potential withholding tax risks, not necessarily in Hong Kong, but in the counterpart jurisdictions involved in a transaction. Although Hong Kong does not impose withholding tax on capital gains, the country from which payment is received, or where the underlying asset is located (if outside Hong Kong), might impose such taxes. These risks can materialize depending on the specific nature of the transaction and the tax laws of the other country. For example, certain payments related to asset disposals might be reclassified or treated as income subject to withholding under foreign laws, even if they would be considered capital gains under a different system. Navigating these cross-border payment flows requires a thorough analysis of the tax rules and any applicable double tax treaties in the foreign jurisdiction.

Another crucial consideration for foreign investors, particularly those with a tangible physical presence or significant activity in Hong Kong, relates to Permanent Establishment (PE) provisions found in Double Tax Treaties. While Hong Kong’s domestic law does not tax capital gains attributable to a PE located here, the existence of a PE can significantly impact how the investor’s residence country taxes income or gains. DTTs often allocate taxing rights over business profits, potentially including certain capital gains depending on the treaty wording, to the source state if a PE exists there. For instance, a DTT might stipulate that gains from the alienation of property forming part of the business property of a PE situated in the source state are taxable in that source state. In Hong Kong’s context, this results in a nil tax liability locally. However, the treaty article might also grant concurrent or residual taxing rights to the residence state. While most of Hong Kong’s DTTs lack specific capital gains articles, their PE clauses, read in conjunction with domestic laws and the investor’s residence country rules, remain important for structuring.

Comparative Analysis: Hong Kong vs. Singapore DTTs

Examining the landscape of Double Tax Treaties (DTTs) in Asia reveals a significant point of divergence when comparing Hong Kong and Singapore, particularly concerning the treatment of capital gains tax (CGT). While both jurisdictions offer attractive tax regimes and possess extensive DTT networks, their approaches to incorporating capital gains provisions within these treaties differ notably. Hong Kong, by virtue of its domestic territorial tax system which generally exempts capital gains from taxation, typically negotiates DTTs that do not include specific articles for taxing capital gains. Taxing rights over such gains are implicitly governed by the domestic laws of the contracting state where the gain is sourced; given Hong Kong’s law, such gains are often not taxable domestically unless considered income from a trading activity.

Singapore, in contrast, has a more nuanced approach to capital gains under its domestic law and, consequently, its DTTs often contain specific capital gains articles. These articles meticulously detail how taxing rights are allocated between Singapore and the treaty partner state for various types of capital gains, such as those derived from immovable property, shares, or other assets. This difference in CGT treaty coverage between Hong Kong and Singapore has a tangible impact on international structuring decisions. Fund managers and international investors evaluating locations for investment vehicles must carefully assess how capital gains derived from their underlying investments will be treated under the specific DTTs available from the chosen jurisdiction.

The presence or absence of a dedicated capital gains article in a DTT can influence critical decisions, from the selection of a holding company location to optimizing tax outcomes on exit strategies. This key distinction contributes to regional investment flow patterns, with certain types of funds or investors potentially preferring one jurisdiction over the other based on the nature of their expected gains and the specific treaty relief offered. Understanding this difference is essential for effective cross-border tax planning within the dynamic Asian financial hubs.

Strategic Considerations for International Tax Planning

Effective tax planning is a crucial component of successful cross-border investment, particularly when leveraging Hong Kong’s distinctive tax regime. A frequently employed strategy involves establishing holding companies or investment vehicles within Hong Kong. This approach aims to harness the jurisdiction’s advantages, notably the absence of a general capital gains tax and access to its expanding network of double tax treaties (DTTs). By routing investments or specific income streams through a Hong Kong entity, investors can potentially benefit from reduced withholding taxes in treaty partner jurisdictions and optimize their overall international tax exposure.

However, merely incorporating a company in a favorable jurisdiction is no longer sufficient on its own to automatically secure DTT benefits. International tax norms and specific treaty clauses have evolved significantly to combat “treaty shopping,” where residents of a third country attempt to improperly obtain treaty benefits intended solely for residents of the actual treaty partners. Modern DTTs and multilateral instruments increasingly incorporate sophisticated anti-avoidance rules, such as the Principal Purpose Test (PPT) or Limitation on Benefits (LOB) clauses. Comprehending and navigating these prevention mechanisms is vital, as tax authorities globally are enhancing scrutiny of cross-border arrangements and requiring taxpayers to demonstrate a clear commercial rationale independent of tax benefits.

A critical element in demonstrating the validity of a structure and mitigating treaty shopping allegations is establishing adequate “substance” in the jurisdiction where the entity is located, such as Hong Kong. This refers to having genuine economic activities, a functional management presence, employees, and physical infrastructure commensurate with the functions performed by the entity. Tax authorities in treaty partner countries are increasingly challenging structures that lack sufficient substance. Relying solely on a mailbox address or nominal directors is typically insufficient; establishing tangible business operations that reflect the entity’s stated purpose is key to supporting treaty claims and reducing the risk of challenges from tax authorities in treaty partner jurisdictions.

Evolving Landscape of Cross-Border Taxation

The environment of international taxation is undergoing continuous transformation, propelled by global initiatives focused on enhancing transparency and ensuring multinational enterprises contribute a fair share of tax in jurisdictions where economic activities and value creation occur. These evolving trends profoundly impact cross-border investments and corporate structures, necessitating adaptation from both businesses and tax authorities. Keeping informed about these developments is paramount for effective international tax planning.

A significant development is the Multilateral Instrument (MLI), developed by the OECD as part of the Base Erosion and Profit Shifting (BEPS) project. The MLI enables jurisdictions to rapidly and efficiently incorporate BEPS-related treaty measures into their existing bilateral double tax treaties without the need for lengthy bilateral renegotiations. Key provisions often introduced via the MLI include measures to counter treaty abuse, notably the Principal Purpose Test (PPT), which can deny treaty benefits if obtaining the benefit was one of the principal purposes of an arrangement or transaction. The MLI is fundamentally reshaping the interpretation and application of tax treaties worldwide.

Another pressing challenge receiving significant global attention is the taxation of the digital economy. Traditional tax rules, often anchored to physical presence requirements, struggle to effectively tax highly digitalized businesses that can generate substantial profits in jurisdictions with minimal or no physical footprint. Ongoing global discussions, particularly within the framework of BEPS 2.0, aim to reallocate taxing rights towards market jurisdictions. This objective is to ensure that profits generated from activities involving users or customers in a country are subject to tax there, even if the company lacks a traditional physical presence.

Building upon the initial BEPS project outcomes, BEPS 2.0 represents a more ambitious reform agenda, primarily through its Two-Pillar Solution. Pillar One focuses on the reallocation of taxing rights for large multinational enterprises to market jurisdictions, while Pillar Two introduces a global minimum corporate tax rate, typically set at 15%, applicable to large MNEs. These initiatives seek to foster a more stable and predictable international tax system while simultaneously addressing concerns about harmful tax competition. These global trends necessitate a careful review of existing cross-border structures and investment flows, including those channeled through established international hubs like Hong Kong.