Tax Planning for Hong Kong Companies with Subsidiaries in Mainland China

📋 Key Facts at a Glance

- Hong Kong Profits Tax: Two-tiered system: 8.25% on first HK$2 million, 16.5% on remainder (corporations)

- China-HK DTA Benefits: Reduced 5% withholding tax on dividends (vs. standard 10%) for qualifying 25%+ shareholdings

- Territorial vs Worldwide: Hong Kong taxes only HK-sourced profits; China taxes worldwide income of resident enterprises

- FSIE Regime: Hong Kong’s foreign-sourced income exemption requires economic substance for dividends, interest, disposal gains

Are you maximizing your tax efficiency while operating across Hong Kong and Mainland China? With over 45,000 Hong Kong companies having subsidiaries in China, navigating the complex interplay between two distinct tax systems presents both challenges and opportunities. This comprehensive guide reveals how to structure your cross-border operations for optimal tax outcomes while maintaining full compliance in both jurisdictions.

Fundamental Tax Differences: Hong Kong vs Mainland China

The first step in effective tax planning is understanding the core differences between Hong Kong’s and Mainland China’s tax systems. These differences create both planning opportunities and compliance challenges that require careful navigation.

Taxation Principles: Territorial vs Worldwide

Hong Kong operates on a territorial basis, meaning only profits sourced in Hong Kong are subject to Profits Tax. This is a critical advantage for companies with international operations. In contrast, Mainland China follows a worldwide taxation principle for resident enterprises, taxing all global income regardless of source. This fundamental difference shapes every aspect of cross-border tax planning.

| Jurisdiction | Taxation Principle | Key Implication |

|---|---|---|

| Hong Kong | Territorial Basis | Only HK-sourced profits taxable; foreign income generally exempt |

| Mainland China | Worldwide Basis | All global income taxable for resident enterprises |

Corporate Tax Rates Comparison

The headline tax rates tell only part of the story. Hong Kong’s two-tiered system offers significant savings for smaller businesses, while China’s preferential rates target specific industries and regions.

| Jurisdiction | Standard Rate | Preferential Rates & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Hong Kong | 16.5% (corporations) | 8.25% on first HK$2 million; 7.5% for unincorporated businesses |

| Mainland China | 25% | 15% for High-New Tech Enterprises; 20% for small low-profit enterprises |

Mastering the China-Hong Kong Double Taxation Arrangement

The Double Taxation Arrangement (DTA) between Mainland China and Hong Kong is your most powerful tool for reducing cross-border tax burdens. Properly leveraged, it can cut withholding taxes by 50% or more on key income streams.

Withholding Tax Benefits Under the DTA

The DTA provides substantial reductions in withholding taxes on payments flowing from China to Hong Kong. Here’s what you need to know:

| Income Type | Standard China Rate | DTA Reduced Rate | Conditions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dividends | 10% | 5% | HK company holds ≥25% equity; beneficial ownership |

| Interest | 10% | 7% | Arm’s length terms; beneficial ownership |

| Royalties | 10% | 7% | For use of IP in China; beneficial ownership |

Avoiding Permanent Establishment Risks

A Permanent Establishment (PE) in China can trigger full corporate tax liability for your Hong Kong company. Common PE triggers include:

- Fixed place of business: Office, factory, or workshop in China

- Construction projects: Lasting more than 6 months

- Dependent agents: Employees or representatives habitually concluding contracts

- Service PE: Employees providing services in China for more than 183 days in any 12-month period

Transfer Pricing: The Critical Compliance Area

With both Hong Kong and China actively enforcing transfer pricing rules, establishing arm’s length pricing for intercompany transactions is non-negotiable. Failure can lead to double taxation, penalties, and reputational damage.

- Conduct Functional Analysis: Document the functions, assets, and risks of each entity in your supply chain. This forms the foundation of your transfer pricing policy.

- Select Appropriate Methods: Choose from Comparable Uncontrolled Price, Resale Price, Cost Plus, Transactional Net Margin, or Profit Split methods based on your business model.

- Prepare Contemporaneous Documentation: Create Master File, Local File, and Country-by-Country Report (if applicable) BEFORE tax authorities request them.

- Consider Advance Pricing Agreements: For complex or high-value transactions, seek binding APA approval from both tax authorities.

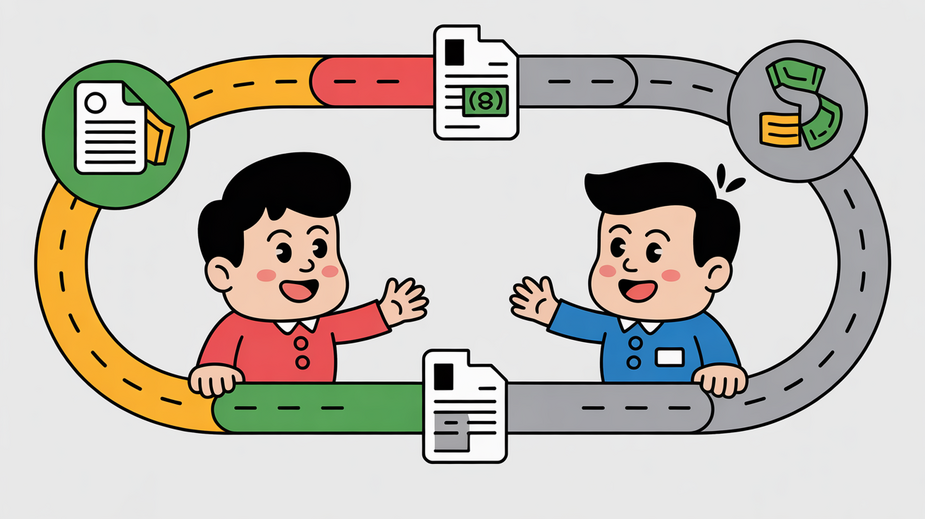

Optimizing Capital and Profit Repatriation

Getting money out of China efficiently requires careful planning. Each repatriation method has different tax implications that must be balanced against regulatory constraints.

| Repatriation Method | Tax Treatment in China | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Dividends | 10% WHT (5% under DTA) | Requires distributable profits; subject to DTA conditions |

| Interest Payments | 10% WHT (7% under DTA); tax-deductible | Subject to thin capitalization rules (2:1 debt-equity ratio) |

| Royalty Payments | 10% WHT (7% under DTA); tax-deductible | Requires valid IP licensing agreement; arm’s length pricing |

| Service Fees | 6% VAT + 25% CIT on net profit | Must demonstrate actual services provided; avoid service PE |

Managing China’s VAT and Fapiao System

China’s Value-Added Tax (VAT) system and the mandatory fapiao (official invoice) system present unique compliance challenges:

- VAT Rates: Generally 13% for goods, 9% for construction/transport, 6% for services

- Input Tax Credits: Recover VAT paid on business purchases to reduce overall tax burden

- Fapiao Management: Official invoices are legally required for all transactions; strict controls needed

- Cross-border VAT: Services provided to overseas entities may qualify for VAT exemption

Future-Proofing Your Cross-Border Strategy

The tax landscape is constantly evolving. Stay ahead of these key developments affecting Hong Kong-China operations:

Greater Bay Area Opportunities

The Guangdong-Hong Kong-Macao Greater Bay Area (GBA) offers unique tax incentives and streamlined procedures. Monitor these developments:

- GBA Talent Tax Subsidy: Preferential individual income tax treatment for eligible talent

- Cross-border Fund Management: Pilot programs for easier capital movement

- Industry-specific Incentives: Tech, finance, and professional services benefits

Global Minimum Tax (Pillar Two)

Hong Kong enacted the Global Minimum Tax regime effective January 1, 2025. This affects multinational groups with revenue ≥ €750 million:

- 15% Minimum Rate: Ensures multinationals pay minimum effective tax

- Income Inclusion Rule (IIR): Parent entities must top up tax to 15%

- HK Minimum Top-up Tax (HKMTT): Hong Kong’s domestic implementation

✅ Key Takeaways

- Leverage the China-HK DTA to reduce withholding taxes by 50% on dividends, interest, and royalties

- Maintain proper economic substance in Hong Kong to benefit from territorial taxation and FSIE regime

- Implement robust transfer pricing documentation to withstand scrutiny from both jurisdictions

- Balance debt and equity financing to optimize thin capitalization rules and interest deductibility

- Stay updated on GBA incentives and global tax developments like Pillar Two implementation

Successfully navigating Hong Kong-China tax complexities requires proactive planning, meticulous documentation, and ongoing monitoring of regulatory changes. By understanding the fundamental differences between the two systems and strategically leveraging available treaties and incentives, you can achieve significant tax savings while maintaining full compliance. Remember that tax planning should align with commercial substance—structure follows strategy, not the other way around.

📚 Sources & References

This article has been fact-checked against official Hong Kong government sources and authoritative references:

- Inland Revenue Department (IRD) – Official tax rates, allowances, and regulations

- Rating and Valuation Department (RVD) – Property rates and valuations

- GovHK – Official Hong Kong Government portal

- Legislative Council – Tax legislation and amendments

- IRD Double Taxation Agreements – China-Hong Kong DTA details

- IRD FSIE Regime – Foreign-sourced income exemption requirements

- IRD Two-tiered Profits Tax FAQ – Detailed guidance on preferential rates

Last verified: December 2024 | Information is for general guidance only. Consult a qualified tax professional for specific advice.