Foundations of Legal Systems Compared

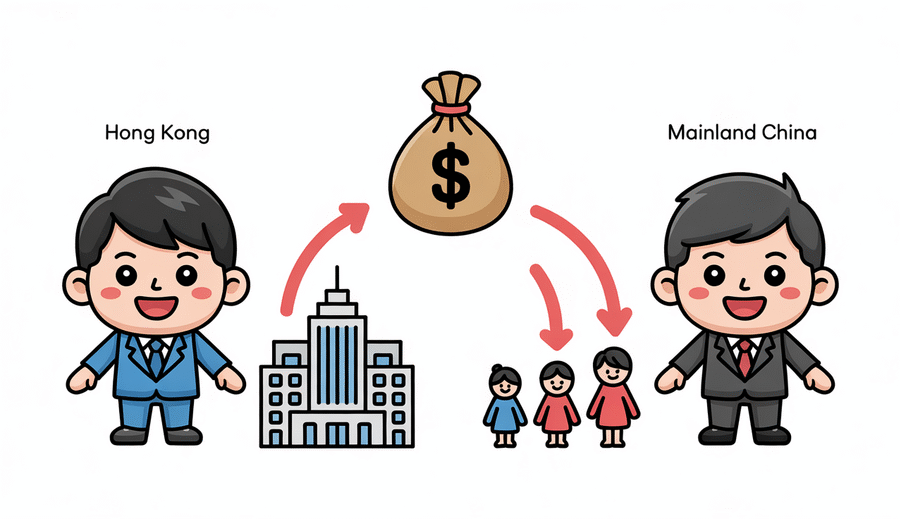

Understanding the fundamental legal systems governing Hong Kong and mainland China is the essential first step when examining inheritance laws for business owners operating across both jurisdictions. Hong Kong operates under a common law framework, a legacy of British colonial rule. This system significantly relies on judicial precedents established by courts, working in conjunction with enacted legislation. The law evolves through the interpretation of past cases, offering adaptability but necessitating careful analysis of prior rulings.

In distinct contrast, mainland China adheres to a civil law tradition. Its legal system is primarily built upon comprehensive, codified statutes. Laws are systematically organized within detailed codes, such as the Civil Code, aiming for predictability and clarity through written rules. This core difference profoundly shapes inheritance structures: common law in Hong Kong typically allows greater flexibility in testamentary wishes, while civil law in mainland China emphasizes prescribed distribution hierarchies and mandatory shares for statutory heirs.

Jurisdiction principles introduce another layer of complexity. Hong Kong generally applies a territorial approach, meaning its laws primarily govern assets physically located within the Special Administrative Region and legal matters occurring there. This is directly relevant for businesses registered or physically situated in Hong Kong, as well as tangible and intangible assets domiciled within its borders.

Mainland China’s legal system, while also considering territorial links, incorporates aspects of nationality-based jurisdiction. This implies that mainland laws can, under certain conditions, apply to Chinese nationals irrespective of their residence or the location of some assets. For business owners with connections to both regions, determining which jurisdiction’s laws apply to their business interests and personal estate upon death requires meticulous analysis, particularly in cross-border situations involving movable property or shares in companies registered elsewhere.

Finally, the disparate legal systems affect how business entities are recognized and treated in an inheritance context. In Hong Kong, companies are typically viewed through a common law lens, with clear regulations governing share ownership, transferability, and the classification of shares as personal property transferable via a will. Succession planning frequently integrates corporate articles and shareholder agreements seamlessly with personal estate planning. Mainland China’s framework for business entities, though modernizing, has specific rules for private enterprises, partnerships, and companies that may interact differently with inheritance law. Grasping how each jurisdiction legally defines and permits the transfer of business interests upon an owner’s death—whether through direct inheritance of shares, partnership stakes, or complex corporate succession mechanisms—is paramount for ensuring a smooth and legally sound transition of a business legacy.

| Feature | Hong Kong | Mainland China |

|---|---|---|

| Legal System | Common Law | Civil Law (Codified) |

| Basis | Precedent, Case Law & Legislation | Codified Statutes (e.g., Civil Code) |

| Jurisdiction Principle | Primarily Territorial | Incorporates Nationality Aspect |

Forced Heirship vs Testamentary Freedom

A central divergence in inheritance laws between mainland China and Hong Kong lies in their fundamental approaches to asset distribution upon death. Mainland China operates under a system that includes elements of forced heirship, a characteristic strongly influenced by its civil law tradition. This legal principle mandates that specified portions of a deceased person’s estate must be allocated to designated statutory heirs, regardless of any contrary wishes expressed by the deceased in a will. Primary statutory heirs typically include the spouse, children, and parents, who are entitled to mandatory shares, substantially limiting the testator’s ability to freely distribute their wealth.

In sharp contrast, Hong Kong’s common law heritage upholds the principle of testamentary freedom. An individual domiciled in Hong Kong generally possesses extensive power to dispose of their assets as they see fit through a validly executed will. While the Inheritance (Provision for Family and Dependants) Ordinance allows certain dependents (such as a spouse, former spouse, child, or other qualifying person) to petition the court for reasonable financial provision if the will does not adequately provide for them, this mechanism is discretionary and does not establish a system of mandatory, fixed shares for statutory heirs akin to the mainland system. The primary authority to direct estate distribution rests with the testator.

The treatment of unmarried partners further illustrates this difference. In mainland China, inheritance laws primarily recognize legally married spouses as statutory heirs entitled to mandatory shares. Unmarried partners typically possess no automatic right to inherit under the statutory framework. In Hong Kong, although an unmarried partner does not automatically inherit under intestacy rules and is not a statutory heir, they may potentially bring a claim under the Inheritance (Provision for Family and Dependants) Ordinance if they were financially dependent on the deceased and the will or intestacy rules fail to provide for them. This process requires a discretionary court application, not an inherent right to a fixed share.

Understanding this fundamental difference between a system prioritizing testamentary freedom (Hong Kong) and one incorporating forced heirship elements (mainland China) is vital for business owners planning their estate across these distinct jurisdictions.

| Feature | Mainland China | Hong Kong |

|---|---|---|

| Forced Heirship | Yes, mandatory shares for legal spouse, children, parents limit testamentary freedom. | No, testamentary freedom is the primary principle. |

| Testamentary Freedom | Limited by statutory mandatory shares. | Broad power to distribute assets via will, subject to potential dependency claims. |

| Unmarried Partners | Generally no automatic inheritance rights under statutory heirship. | No automatic inheritance rights, but may potentially claim under dependency ordinance. |

Business Succession Planning Mechanisms

Inheritance for business owners presents unique challenges, especially when navigating the differing legal landscapes of mainland China and Hong Kong. In mainland China, the framework for business succession, particularly within private enterprises, often sees a strong emphasis on family inheritance. While legal provisions exist for wills, the practical application and societal norms can result in the business primarily passing to statutory heirs—typically spouses and children—sometimes regardless of their suitability or involvement in business operations. This family-centric approach can influence strategic planning, potentially complicating transitions to non-family management or key employees who were integral to the business’s success.

In contrast, Hong Kong’s common law system offers significantly greater flexibility for business owners planning succession. Here, the focus shifts more towards the structure of the business entity itself, particularly limited companies. Owners have wide latitude to determine how their shares, and consequently control of the business, are transferred upon death. This can be explicitly stipulated in a will, allowing for shares to be bequeathed to family members, business partners, employees, or even unrelated parties. Hong Kong’s legal environment facilitates the use of various corporate mechanisms and testamentary instruments to ensure a smoother transition aligned with the owner’s specific wishes for the business’s future leadership and ownership structure.

A crucial tool in business succession planning for enterprises with multiple owners, regardless of jurisdiction, is a well-drafted shareholder agreement. These contracts can contain vital provisions governing the transfer of shares upon the death of a shareholder, such as buy-sell arrangements, rights of first refusal, or mechanisms for valuing the deceased’s stake. In Hong Kong, such agreements are generally strongly upheld as binding contractual obligations, providing a clear roadmap for succession that complements testamentary dispositions.

While shareholder agreements are also utilized in mainland China, their interaction with mandatory inheritance rules and the emphasis on family succession can introduce complexities. Potential disputes may arise if agreements are not carefully drafted to align with or effectively navigate mainland legal requirements. Understanding these subtle differences in the recognition and enforcement of shareholder agreements within the context of inheritance is paramount for effective cross-border business succession planning.

| Aspect | Mainland China | Hong Kong |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Focus in Inheritance | Family (Statutory Heirs) | Owner’s Will & Corporate Structure |

| Key Legal Framework | Civil Code & Related Laws | Common Law & Company Law |

| Shareholder Agreement Interaction | Can be complex with family inheritance rules | Generally strongly upheld as contract |

| Flexibility in Choosing Successor | Limited by forced heirship & family priority | High flexibility through wills & corporate tools |

Tax Implications for Inherited Enterprises

For business owners planning inheritance across Hong Kong and mainland China, tax implications represent a significant point of difference. While neither jurisdiction currently imposes a broad, general inheritance tax on individual estates, the potential for taxation on business asset transfers and the underlying tax frameworks diverge.

In mainland China, although a general inheritance tax is not widely applied, the legal basis for its future implementation exists. Regarding businesses, transferring assets or shares via inheritance can trigger other transaction-based taxes depending on the entity type and asset class (e.g., real estate, equity). These may include income tax on deemed gains, stamp duty, or land value increment tax. Inheriting a business on the mainland can therefore involve navigating various specific transaction-related tax liabilities.

Hong Kong presents a clear contrast in this regard. Since the abolition of estate duty in 2006, no tax is levied on the value of a deceased person’s estate, including business assets. Assets passing via will or intestacy are explicitly free from estate or inheritance tax within the territory. This creates a simpler tax environment for beneficiaries inheriting business interests located in Hong Kong, removing a major potential financial burden at the point of succession.

Asset valuation methodologies are also influenced by the respective tax contexts. In mainland China, particularly for taxable transfers, valuation may necessitate formal appraisals guided by state or tax regulations. In Hong Kong, valuation for probate purposes (determining estate size for administrative fees) is an administrative requirement for distribution, not a calculation for inheritance tax. Professional valuers determine fair market value based on standard industry practices.

This difference in tax approach constitutes a critical factor in cross-border inheritance planning, highlighting Hong Kong’s more straightforward tax environment specifically concerning inherited estates and business assets.

| Feature | Mainland China | Hong Kong |

|---|---|---|

| Inheritance/Estate Tax | Framework exists; transaction/asset taxes possible on business transfer. | No estate/inheritance tax since 2006. |

| Asset Valuation (Inheritance Context) | Formal appraisals guided by state/tax rules for taxable transfers. | Professional valuation for probate; not tax-driven. |

Cross-Border Inheritance Complexities

Navigating inheritance matters when assets or beneficiaries span both Hong Kong and mainland China introduces a distinct layer of complexity compared to purely domestic estates. Business owners with holdings in both jurisdictions face challenges rooted in the fundamental differences between their legal systems and regulatory environments. Effective planning requires addressing how assets located under different legal umbrellas will be handled upon succession.

One critical strategy for managing assets across this divide is the implementation of dual-will structures. Instead of a single, complex will attempting to cover assets governed by disparate legal frameworks, creating separate wills—one specifically tailored for Hong Kong assets under its common law system and another for mainland China assets governed by its civil code—can significantly streamline the probate process in each location. This approach acknowledges the territorial nature of inheritance laws and helps ensure compliance with specific local requirements, potentially preventing lengthy disputes and complications. It is crucial that these wills are carefully drafted and coordinated to avoid conflicts or accidental revocation.

A major hurdle in cross-border inheritance is the limited mutual recognition and enforcement of probate grants or judgments between Hong Kong and mainland China in inheritance cases. While agreements exist for civil and commercial judgments, inheritance matters often fall outside these frameworks, or the process for recognition is complex and uncertain. Consequently, securing a grant of probate or administration in one jurisdiction does not automatically mean it will be directly enforceable in the other. Typically, a separate application following local legal procedures is required in each jurisdiction where significant assets are located.

Furthermore, the transfer of inherited funds or the proceeds from the sale of inherited business assets from mainland China to beneficiaries residing in Hong Kong or elsewhere can be complicated by China’s foreign exchange controls. While provisions exist for the repatriation of legally inherited funds, the process involves navigating stringent regulations, including documentation requirements, conversion limits, and approval processes through designated banks. Converting significant amounts of Renminbi (RMB) into foreign currency and remitting it abroad can be time-consuming and requires strict adherence to prevailing capital control policies, adding another layer of administrative burden and potential delay to the inheritance process.

Effectively managing inheritance for business owners with interests in both Hong Kong and mainland China demands a thorough understanding of these cross-border complexities. Addressing issues such as the choice of will structure, the potential need for local legal action to enforce inheritance rights, and navigating currency regulations are essential steps in ensuring a smoother transfer of business legacies and personal wealth across this unique border.

Probate Processes and Timelines

Navigating the legal procedures after a business owner’s passing is a critical phase in the inheritance process. For businesses spanning Hong Kong and mainland China, understanding the distinct approaches to probate and asset transfer is essential. The administrative journey, from validating a will to distributing assets, differs significantly between the two jurisdictions, impacting both the complexity and the timeline involved.

In mainland China, the inheritance process often relies heavily on notarization. Validating a will, proving relationships between the deceased and heirs, and confirming asset ownership typically necessitates extensive notarization procedures at designated notary offices. This step is a fundamental gateway to initiating the transfer of inherited property, including business interests. While intended to ensure authenticity and prevent fraud, these rigorous notarization requirements introduce bureaucracy and can potentially extend the overall duration of the settlement process.

Conversely, Hong Kong employs a system rooted in common law, focused on obtaining a Grant of Probate (if there is a valid will) or Letters of Administration (if there is no will) from the High Court. While this process still involves legal procedures, court applications, and submitting comprehensive documentation, the primary focus is on the judicial validation of the deceased’s wishes and confirming the legal authority of the appointed executor or administrator to manage the estate. Hong Kong’s court-based process is often described as more streamlined, particularly for straightforward cases involving assets clearly situated within the territory.

The disparity in procedural requirements naturally contributes to differences in typical settlement durations. While numerous factors influence the timeline in both regions, including the complexity of the estate, the number of beneficiaries, and any potential disputes, the reliance on extensive notarization and potentially administrative approvals in the mainland can sometimes result in a longer administrative lead time. Hong Kong’s court-based system, while subject to court backlogs, can often progress more quickly once the initial application is complete and processed.

Ultimately, successfully navigating these distinct probate and administrative processes requires careful planning, detailed knowledge of the specific requirements in each territory, and often professional legal assistance in both jurisdictions to ensure a smoother transition of business assets and personal wealth.

| Feature | Mainland China | Hong Kong |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Legal Mechanism | Notarization / Administrative Process | Grant of Probate / Letters of Administration (Court-based) |

| Authority | Notary Publics, Local Bureaus, potentially Courts | High Court |

| Key Documentation Step | Extensive notarized proofs required for various stages | Court application & judicial validation of will/executor authority |

| General Process Speed | Can be slower due to administrative & notarization requirements | Often faster once initial court application progresses, for straightforward estates |