Why Your Business Structure Matters: Tax Implications of Branches vs. Subsidiaries in Hong Kong

📋 Key Facts at a Glance

- Tax Rates: Hong Kong corporations pay 8.25% on first HK$2 million profits, 16.5% on remainder (2024-25)

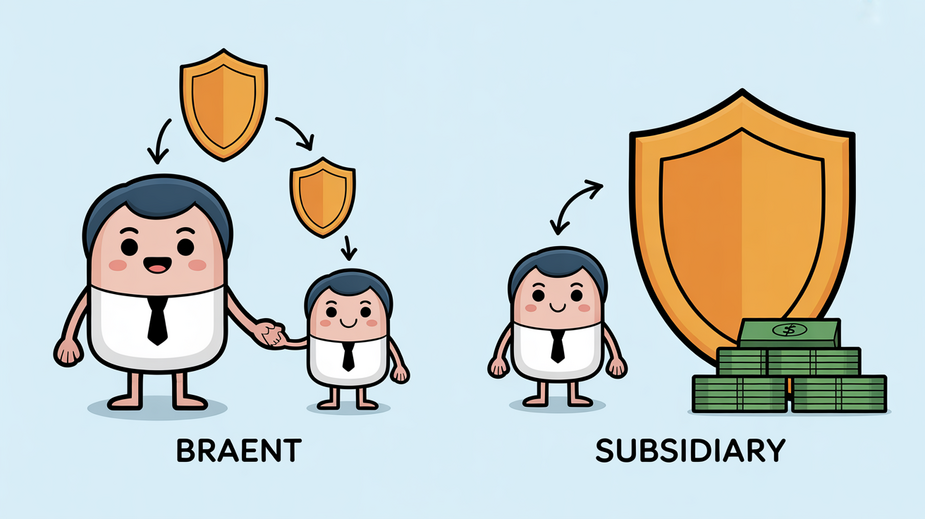

- Legal Status: Branches are extensions of parent companies; subsidiaries are separate legal entities

- Liability Protection: Subsidiaries offer limited liability; branches expose parent companies to unlimited liability

- Tax System: Hong Kong uses territorial taxation – only Hong Kong-sourced profits are taxable

- Compliance: Subsidiaries require full local audits; branches have simpler local reporting

Did you know that choosing between a branch and a subsidiary in Hong Kong could mean the difference between unlimited liability exposure and protected assets? Or that your choice could affect whether you pay 8.25% or 16.5% on your profits? For international businesses expanding into Asia, Hong Kong offers a strategic gateway, but the structure you choose – branch or subsidiary – creates dramatically different tax outcomes, legal protections, and operational realities. This decision isn’t just administrative paperwork; it’s a foundational strategic choice that will shape your company’s financial health, risk profile, and growth potential for years to come.

The Strategic Decision: Why Your Business Structure Matters

When expanding into Hong Kong, your choice between establishing a branch or incorporating a subsidiary is more than just a legal formality – it’s a strategic decision with profound implications for your tax burden, liability exposure, and operational flexibility. Hong Kong’s business-friendly environment, with its simple tax system and territorial taxation principle, makes it an attractive destination, but the optimal structure depends entirely on your specific business goals, risk tolerance, and long-term plans.

Branches: The Extension Model

A branch office in Hong Kong is not a separate legal entity – it’s an extension of its foreign parent company. Think of it as your company’s arm reaching into Hong Kong, but legally, it’s still part of your main body. This fundamental characteristic shapes every aspect of branch operations.

Key Characteristics of Branches

- No Separate Legal Identity: The branch operates under the parent company’s name and legal personality

- Unlimited Liability: The parent company is fully liable for all branch debts and obligations

- Simpler Setup: Registration involves filing with the Companies Registry, but no new company is created

- Consolidated Reporting: Financial results are typically consolidated into parent company accounts

- Tax Treatment: Profits are taxed as part of parent company’s income in its home jurisdiction

When a Branch Makes Sense

Consider establishing a branch if:

- Testing the Market: You want to explore Hong Kong with minimal initial commitment

- Short-term Projects: You have a specific, time-limited project or contract

- Parent Company Protection: Your parent company is in a jurisdiction with favorable tax treatment of foreign branch profits

- Administrative Simplicity: You want to avoid the complexity of maintaining a separate legal entity

Subsidiaries: The Independent Entity Model

A subsidiary is a completely separate legal entity incorporated under Hong Kong law. It’s like creating a new, independent company that happens to be owned by your parent company. This separation creates both opportunities and obligations that differ fundamentally from the branch model.

Key Advantages of Subsidiaries

- Limited Liability: Parent company risk is limited to its investment in the subsidiary

- Separate Legal Identity: Can own property, enter contracts, and sue/be sued in its own name

- Local Profit Retention: Profits can be retained in Hong Kong and reinvested locally

- Tax Optimization: Can fully leverage Hong Kong’s territorial tax system and two-tiered profits tax rates

- Investor Appeal: Easier to attract external investment or partners

When a Subsidiary is the Better Choice

Opt for a subsidiary when:

- Long-term Commitment: You’re serious about establishing a permanent presence in Hong Kong

- Risk Management: You need to protect parent company assets from local operational risks

- Local Banking: You want to establish strong local banking relationships and credit facilities

- Exit Strategy: You may want to sell the business or attract investors in the future

- Tax Efficiency: You want to maximize benefits from Hong Kong’s territorial tax system

Tax Implications: A Side-by-Side Comparison

The tax treatment of branches versus subsidiaries creates some of the most significant differences between the two structures. Understanding these nuances is crucial for making an informed decision.

| Tax Aspect | Branch | Subsidiary |

|---|---|---|

| Hong Kong Profits Tax | 15% on net assessable value (same as property tax rate for non-corporate) | 8.25% on first HK$2M, 16.5% on remainder (corporations) |

| Taxation Timing | Profits taxed immediately in parent’s jurisdiction | Profits taxed locally; parent taxed only on dividends |

| Loss Utilization | Can offset against parent’s global profits (subject to home country rules) | Contained within subsidiary; offsets against future profits only |

| Double Taxation Relief | Depends on parent’s jurisdiction and tax treaties | Can benefit from Hong Kong’s 45+ comprehensive double taxation agreements |

| Transfer Pricing | Head office expense allocations scrutinized | Intercompany transactions subject to arm’s length principle |

Understanding the Two-Tiered Profits Tax

Hong Kong’s two-tiered profits tax system, introduced in 2018/19, offers significant tax savings for qualifying businesses:

| Entity Type | First HK$2M Profits | Remaining Profits |

|---|---|---|

| Corporations | 8.25% | 16.5% |

| Unincorporated Businesses | 7.5% | 15% |

Legal Liability: Protecting Your Assets

The liability protection difference between branches and subsidiaries is perhaps the most critical consideration for risk-averse businesses.

| Liability Aspect | Branch | Subsidiary |

|---|---|---|

| Legal Status | Extension of Parent Company | Separate Legal Entity |

| Parent Liability | Unlimited – full exposure | Limited to investment amount |

| Asset Protection | Parent’s global assets at risk | Parent’s assets protected |

| Contractual Risk | Parent liable for all contracts | Subsidiary liable for its contracts |

| Legal Disputes | Parent can be sued directly | Generally limited to subsidiary |

Compliance and Administrative Requirements

The compliance burden differs significantly between branches and subsidiaries, affecting both cost and operational complexity.

Branch Compliance Requirements

- Registration: File with Companies Registry within 1 month of establishment

- Annual Renewal: Renew branch registration annually

- Tax Filing: File profits tax returns for Hong Kong-sourced income

- Financial Reporting: Maintain proper accounts; may need to file audited accounts depending on parent’s requirements

- Business Registration: Obtain Business Registration Certificate

Subsidiary Compliance Requirements

- Incorporation: Full company registration with Articles of Association

- Annual Audit: Mandatory annual audit by Hong Kong CPA

- Annual Return: File annual return with Companies Registry

- Tax Returns: Separate profits tax returns filed annually

- Financial Statements: Prepare standalone financial statements

- Director Compliance: Maintain registered office and company secretary

Long-Term Strategic Considerations

Your choice between branch and subsidiary should align with your long-term business strategy. Consider these future-oriented factors:

Scalability and Growth

Subsidiaries generally offer better scalability. As a separate legal entity, a subsidiary can:

- Raise capital independently through equity or debt

- Establish its own credit history and banking relationships

- Enter into joint ventures or partnerships more easily

- Expand regionally from a Hong Kong base

Exit Strategies and M&A

If you might sell your Hong Kong operations in the future, a subsidiary structure is vastly superior:

- Clean Transfer: Selling shares is simpler than transferring branch assets

- Clear Valuation: Standalone financials make valuation easier

- Investor Appeal: Private equity and strategic buyers prefer subsidiaries

- Due Diligence: Separate legal entity simplifies the process

Regulatory Future-Proofing

Consider how global tax developments might affect your structure:

- Global Minimum Tax: Hong Kong enacted Pillar Two legislation effective January 1, 2025, applying 15% minimum tax to large MNEs

- FSIE Regime: Hong Kong’s Foreign-Sourced Income Exemption regime requires economic substance for certain income types

- Double Taxation Agreements: Hong Kong has 45+ comprehensive DTAs that can benefit subsidiaries

Decision Framework: Which Structure is Right for You?

Use this decision framework to guide your choice:

- Assess Your Risk Tolerance: Can you accept unlimited liability? If not, choose a subsidiary.

- Evaluate Tax Implications: Consider both Hong Kong taxes and your home country’s treatment of foreign income.

- Consider Time Horizon: Short-term projects favor branches; long-term commitments favor subsidiaries.

- Review Compliance Capacity: Do you have resources for full subsidiary compliance?

- Plan for the Future: Consider growth, fundraising, and potential exit strategies.

✅ Key Takeaways

- Branches offer simplicity but expose parent companies to unlimited liability and may face complex international tax treatment

- Subsidiaries provide liability protection and can fully leverage Hong Kong’s favorable tax system, including the two-tiered profits tax rates

- Tax rates matter: Corporations pay 8.25% on first HK$2M profits, 16.5% on remainder – but only one entity per group gets the lower tier

- Compliance differs: Subsidiaries require full local audits and reporting; branches have simpler local requirements

- Think long-term: Subsidiaries are better for scalability, fundraising, and eventual exit strategies

- Hong Kong’s territorial system means only locally-sourced profits are taxable – structure your operations accordingly

The choice between a branch and a subsidiary in Hong Kong is one of the most important decisions you’ll make when expanding into Asia. While branches offer initial simplicity, subsidiaries provide the liability protection, tax optimization, and strategic flexibility needed for long-term success. Remember that this decision should align with your overall business strategy, risk tolerance, and growth plans. Given the complexity of international tax implications and the permanence of this structural choice, consulting with experienced Hong Kong tax and legal professionals is highly recommended to ensure your structure supports rather than hinders your business objectives.

📚 Sources & References

This article has been fact-checked against official Hong Kong government sources and authoritative references:

- Inland Revenue Department (IRD) – Official tax rates, allowances, and regulations

- Rating and Valuation Department (RVD) – Property rates and valuations

- GovHK – Official Hong Kong Government portal

- Legislative Council – Tax legislation and amendments

- IRD Profits Tax Guide – Official profits tax rates and regulations

- IRD Double Taxation Agreements – Comprehensive list of Hong Kong’s DTAs

- Companies Registry – Company and branch registration requirements

Last verified: December 2024 | Information is for general guidance only. Consult a qualified tax professional for specific advice.